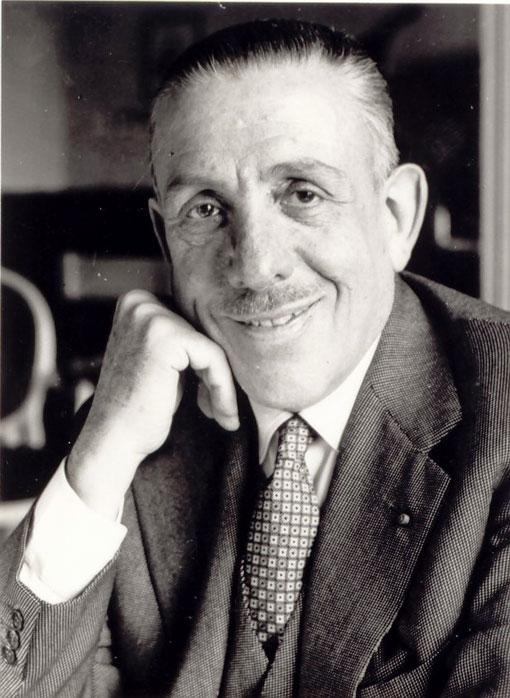

Francis Poulenc

Paris, 1899 - 1963

Born in Paris to a very well-off family—his father was the famed industrialist Poulenc of the Rhône-Poulenc company—, Francis Poulenc began to study piano with his mother at the age of 5. In 1915, he went to study with Ricardo Viñes, who introduced him to the who’s who of the Paris musical avant-garde: Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Satie… and to poets Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Éluard, and Max Jacob… His first work, Rhapsodie nègre (1917), enraged the jury at the Conservatoire, which closed its doors to him forever. The work would nevertheless go on to bring him enduring success. A member of what Cocteau called the “Group of Six” (with Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, and Germaine Taillefer), he was nicknamed the “bad boy” of music for his many homosexual adventures. He said that he “composed by instinct” and that his music of the time was almost always light-hearted. He therefore did not dabble in traditional genres, save for his 2 posthumous sonatas—one for oboe and piano, the other for clarinet and piano. According to his fancy (and to commissions), he composed ballets, aubades, eccentric concertos, and several other pieces for unusual groups, with a pen whose verve was equalled only by its abundance and diversity. His 3 operas are perfect examples: the irresistibly scathing humour of Les Mamelles de Tirésias, the serious drama of Dialogues des carmélites, and the psychological monodrama La voix humaine.

He toured frequently with Pierre Bernac, his friend and favourite performer (he wrote 90 of his some 145 songs for him), notably in America where he had two fateful encounters—with composer Samuel Barber and singer Leontyne Price, who would always support his work (in fact, Leontyne Price appeared in the American premiere of Dialogues des carmélites in San Francisco). After his father’s death (1935), Poulenc made a profound and sincere return to Catholicism, which would colour a good part of his work from that point forward (Gloria, Stabat Mater, and Dialogues des carmélites). Resolutely loyal to the aesthetic of the Golden Twenties and Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, to the spirit of the surrealists and of Dada, he remained impervious to other trends. Despite, or because of, his marginality, and much like many of the French masters, his stature was always that of a unique composer, as atypical as he is universally recognized and appreciated.